Carbide end mills are a brilliant solution for cutting hardened steel, offering superior durability and efficiency where traditional tools struggle.

Have you ever looked at a piece of hardened steel and wondered how on earth you’re supposed to machine it? It’s like trying to carve granite with plastic! Many beginner machinists, myself included when I first started out, might shy away from these tough materials. But the truth is, with the right tools and techniques, machining hardened steel is not only possible but can be remarkably straightforward. The secret weapon? The carbide end mill. If you’ve been struggling, or just curious about tackling hardened steel, you’re in the right place. We’re going to break down exactly why a carbide end mill is so special for this job and how you can use it effectively to achieve those impressive machining results.

Why Is Machining Hardened Steel So Tricky?

Hardened steel is, well, hard! That’s its defining characteristic. This hardness is achieved through a process called heat treatment, where steel is heated to a high temperature and then rapidly cooled (quenched). This changes its internal structure, making it much tougher and more resistant to wear. While fantastic for the end product – think gears, tooling, shafts, and cutting implements – it makes the machining process a real challenge for conventional tools like High-Speed Steel (HSS) end mills. HSS tools can quickly overheat, lose their cutting edge, and even break when encountering such resistant material.

The heat generated during machining is a huge problem. As the cutting tool scrapes against the hardened steel, friction creates intense heat. This weakens the cutting edge of the tool, causing it to dull rapidly. A dull tool then requires more force to cut, which creates even more heat, leading to a vicious cycle. Eventually, the tool can fail catastrophically – a chipped or broken end mill that can damage your workpiece and your machine, not to mention the frustration it causes. For beginners, this can be a disheartening experience that discourages them from exploring more advanced machining projects.

Enter the Carbide End Mill: The Hardened Steel Specialist

This is where the carbide end mill truly shines. Carbide, specifically tungsten carbide, is a composite material formed by combining tungsten carbide particles with a binder metal, usually cobalt. This unique composition gives it properties that are vastly superior to HSS for cutting hard materials.

What Makes Carbide So Much Better?

- Extreme Hardness: Carbide is significantly harder than HSS. This means it can maintain its cutting edge much longer when working with very hard materials like hardened steel (often up to 60 HRC and even higher).

- High Heat Resistance: Carbide can withstand much higher temperatures than HSS before losing its hardness. This is crucial for machining hardened steel, where significant heat is generated. It allows for faster cutting speeds and feeds without rapidly degrading the tool.

- Rigidity: Carbide tools are generally more rigid than HSS tools of the same size. This means they are less prone to deflection, leading to more accurate cuts and a lower risk of chipping or breaking, especially when plunging or taking heavier cuts.

- Better Surface Finish: Due to their hardness and rigidity, carbide end mills can often produce a smoother surface finish on the workpiece compared to HSS.

While carbide is more brittle than HSS (meaning it can chip if subjected to sudden impacts or excessive side-loading), its benefits for hardened steel machining are undeniable. For hobbyists and aspiring machinists, understanding and using carbide end mills can unlock a whole new level of project possibilities.

Choosing the Right Carbide End Mill for Hardened Steel

Not all end mills are created equal, and for hardened steel, specific features matter. When you’re looking for a “carbide end mill 1/8 inch 1/2 shank standard length for hardened steel hrc60,” you’re already on the right track. Let’s break down what those specifications mean and why they’re important.

Key Specifications Explained:

- Carbide: This is your primary material choice for hardness and heat resistance.

- End Mill Type: For hardened steel, you’ll typically want a “square” or “corner radius” end mill. Ball-end mills are for creating contours, and should generally be avoided for plunge cutting into hardened steel due to potential chipping.

- Coating: While not always necessary for beginners, specialized coatings like TiAlN (Titanium Aluminum Nitride) or AlTiN (Aluminum Titanium Nitride) can significantly improve performance by adding lubricity and further enhancing heat and wear resistance. For general hardened steel work, an uncoated carbide end mill is often sufficient, but a coated one will last longer and cut better.

- Number of Flutes: This refers to the number of cutting edges around the tool.

- 2 Flutes: Excellent for clearing chips, especially in harder materials. They offer more space for chip evacuation, reducing the risk of chip recutting and overheating. Great for plunging operations.

- 3 Flutes: A good all-around balance between cutting performance and chip evacuation.

- 4 Flutes: Best for finishing operations or when you need a smoother surface finish. However, they can pack up with chips more easily when plunging or roughing in tough materials, so use with caution or with excellent chip evacuation.

- Material Hardness Rating (HRC): This is crucial. End mills are rated for the hardness of the material they can effectively cut. For steel hardened to 60 HRC, you need an end mill specifically designed for this. Look for end mills rated for “hardened steel” or specific HRC ranges (e.g., up to 60 HRC, or even higher).

- Diameter (e.g., 1/8 inch): This is the cutting diameter of the end mill. For smaller, detailed work, a 1/8-inch end mill is common. It’s a good size for many hobbyist projects.

- Shank Diameter (e.g., 1/2 inch): This is the diameter of the part of the end mill that goes into the collet or tool holder. A 1/2-inch shank is standard for many milling machines and provides good rigidity. Using the largest shank diameter that fits your machine and desired cut is generally a good idea for stability.

- Length: “Standard length” refers to the overall length and effective cutting length. For most general milling, a standard length is perfectly adequate. Longer reach end mills are for accessing deeper features.

For hardened steel, especially when doing roughing or plunge cuts, a 2-flute or 3-flute end mill is often preferred.

A Word on Corner Radius

Standard end mills have a sharp 90-degree corner, called a “square” end mill. While versatile, these sharp corners can be prone to chipping when cutting very hard materials, especially during plunge cuts or when encountering slight variations in material hardness. An end mill with a small corner radius (e.g., 0.010″ or 0.020″) can significantly improve tool life and chip control by strengthening the cutting edge and distributing stress more evenly.

For beginners tackling hardened steel, consider starting with a square end mill or one with a very small corner radius. If you plan on deeper cuts or more aggressive machining, a small corner radius is often a wise choice.

Essential Speeds and Feeds for Carbide on Hardened Steel

The general rule of thumb for machining hardened steel with carbide is to use higher spindle speeds (RPM) and lower feed rates compared to machining softer materials. This is because carbide excels at high-speed cutting and can handle the heat generated, but it’s also more brittle, so aggressive feed rates can cause it to chip.

Surface Speed to RPM Conversion

The fundamental concept is Surface Speed (SFM or SMM – Surface Meters per Minute). This is the speed at which the cutting edge of the tool is moving across the material. Different tool materials and workpiece materials have recommended surface speed ranges. For carbide cutting hardened steel (e.g., HRC 55-60), typical surface speeds might range from 150 to 300 SFM (45 to 90 SMM), but this can vary greatly depending on the specific carbide grade, coating, and presence of coolant.

You convert surface speed to spindle speed (RPM) using the following formula:

RPM = (Surface Speed × 12) / (Tool Diameter × π)

Or using metric:

RPM = (SMM × 1000) / (Tool Diameter × π)

Where:

- RPM = Revolutions Per Minute of the spindle

- Surface Speed = Recommended surface speed in SFM (Surface Feet per Minute) or SMM (Surface Meters per Minute)

- Tool Diameter = Diameter of the end mill in inches or millimeters

- π (Pi) = Approximately 3.14159

Example: For a 1/8-inch (0.125″) carbide end mill cutting hardened steel at 200 SFM:

RPM = (200 × 12) / (0.125 × 3.14159) ≈ 6111 RPM

For a 1/8-inch (3.175mm) carbide end mill cutting hardened steel at, say, 60 SMM (a conservative starting point):

RPM = (60 × 1000) / (3.175 × 3.14159) ≈ 6030 RPM

Feed Rate Considerations

The feed rate is how fast the tool moves into the material or along its path. For carbide on hardened steel, you’ll typically use a lower feed rate per tooth (IPT or IPMM) than you would with HSS. This is often expressed as chip load, which is the thickness of the chip being removed by each cutting edge (flute).

Feed Rate (IPM) = RPM × Number of Flutes × Chip Load (IPT)

Getting the chip load right is crucial for tool life and performance. Too small a chip load, and the carbide may rub rather than cut, leading to premature dulling and increased heat. Too large a chip load, and you risk chipping the carbide or exceeding the machine’s rigidity. For a 1/8-inch carbide end mill in hardened steel, chip loads might range from a tiny 0.0005″ to 0.0015″ IPT, again, depending on the specific tool, material, and operation.

Recommended Starting Points (Always Test!)

These are general guidelines and may need adjustment based on your specific machine, the exact hardness of your steel, the presence and type of coolant, and the specific brand/grade of your carbide end mill. Always consult the tool manufacturer’s recommendations if available.

| Operation | Material Hardness | End Mill Type | RPM (Approx. for 1/8″ tool) | Chip Load IPT (Approx.) | Depth of Cut (DoC) | Width of Cut (WoC) | Coolant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roughing/Slotting | Up to 60 HRC | 2-Flute Carbide | 5000-7000 RPM | 0.0008″ – 0.0012″ | 0.010″ – 0.030″ | 0.050″ – 0.100″ (or full slot) | Flood or Mist |

| Finishing | Up to 60 HRC | 4-Flute Carbide (small corner radius recommended) | 6000-8000 RPM | 0.0006″ – 0.0010″ | 0.005″ – 0.010″ | 0.020″ – 0.050″ | Mist or Dry (with excellent chip blowing) |

Important Notes:

- Rigidity is Key: Use the shortest possible tool extension (sticking as much of the shank into the collet as possible) to maximize rigidity.

- Start Conservatively: It’s always better to start at the lower end of the recommended RPM and chip load, then gradually increase them while listening to the cut and observing chip formation.

- Chip Evacuation: This is paramount. Ensure your machine can effectively clear chips away from the cutting zone. For smaller machines, air blast or mist coolant is often best. For plunge cuts, 2-flute end mills are highly recommended.

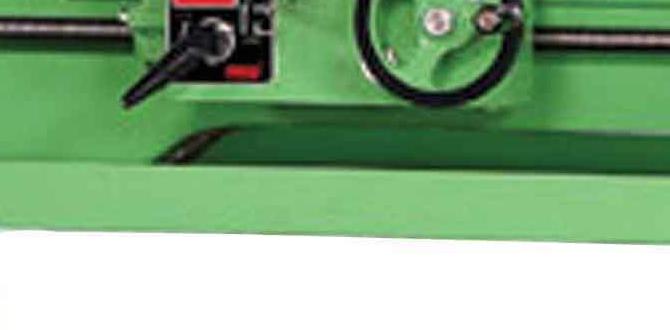

- Machine Capabilities: Ensure your milling machine can accurately achieve and maintain the required high RPM with sufficient rigidity. A machine with a weak spindle or poor rigidity will struggle.

- Coolant/Lubrication: For hardened steel with carbide, flood coolant or a high-quality mist coolant is highly beneficial. It reduces heat, lubricates the cut, and helps evacuate chips. Some specialized carbide tools are designed for dry machining, but this requires very precise control.

A great resource for machining data, including speeds and feeds, is often provided by the tool manufacturers themselves. For instance, companies like Kennametal offer online calculators and guidelines for their tooling.

Essential Machining Setup and Safety Practices

Working with carbide end mills on hardened steel demands meticulous setup and a strong focus on safety. Because these operations can be unforgiving, ensuring everything is just right before you start is crucial for both your success and your well-being.

Workpiece Clamping: The Foundation of Your Cut

A securely held workpiece is non-negotiable. Hardened steel is tough, and the forces exerted by the milling cutter can be substantial. Even a slight movement of the workpiece can lead to:

- Tool Breakage: If the cutter suddenly encounters a loose spot, it can snag and break.

- Inaccurate Cuts: The workpiece shifting will result in dimensions that are off.

- Damage to Machine Components: Loosely held workpieces can cause violent collisions.

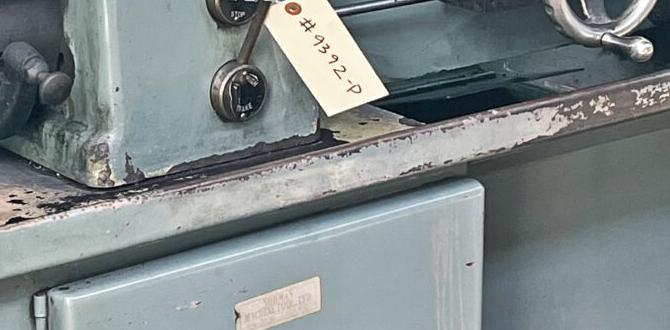

Use robust clamping methods. For smaller parts, vises with hardened jaws or specialized fixtures are ideal. For larger parts, ensure you have adequate clamps, T-nuts, and studs to hold it firmly to the milling table. Never rely on just one clamp if more are feasible. If you’re unsure about workholding, consult resources like AMT’s guide on workholding.

Tool Holder and Collet Selection

The connection between your spindle and the end mill is critical. For carbide end mills, especially smaller ones like an 1/8-inch, a high-quality tool holder and collet system is essential for accuracy and rigidity.

- Tool Rigidity: Use the shortest possible tool protrusion from the collet. The more the tool sticks out, the more it can deflect, increasing the risk of chipping or breaking.

- Collet Condition: Ensure your collets are clean, free of debris, and not excessively worn. A worn collet won’t provide consistent gripping force. For a 1/8-inch end mill, use a collet that is very close to that size (e.g., 1/8″ or 3mm), rather than an adapter sleeve.

- Runout: Minimize runout (wobble) of the tool. Excessive runout will cause the tool to cut unevenly, leading to chatter, poor finish, and premature wear.

Coolant and Chip Evacuation

As discussed, coolant is your best friend when machining hardened steel with carbide. It dissipates heat, lubricates the cut, and helps wash away chips. Whether you use flood coolant, a mist system, or even a specialized paste lubricant, ensure it’s applied effectively to the cutting zone.

For smaller machines or specific operations like slotting, proactive chip evacuation is critical. Compressed air can help blow chips away, especially if you’re running dry or with a mist system. Avoid letting chips build up in the flutes of the end mill, as this can cause it to overheat and break.

Safety First: Always!

Machining, especially with hard materials, carries inherent risks. Make safety your top priority:

- Eye Protection: Always wear ANSI- Z87.1 compliant safety glasses or a full face shield. Flying chips, even small ones, can cause serious eye injury.

- Machine Guarding: Ensure all machine guards are