Quick Summary: For wood, a fly cutter offers a single, sharp edge for cleaner, broader cuts, ideal for surfacing. A face mill uses multiple inserts, providing more power and speed for roughing and heavy material removal, though it can be more complex to set up. Choose based on your project’s needs for finish quality and material removal.

Hey there, workshop warriors! Daniel Bates here from Lathe Hub. Ever found yourself staring at a piece of rough lumber, wondering how to get it perfectly flat and smooth? Or maybe you’ve seen terms like “face mill” and “fly cutter” thrown around and felt a little lost. Don’t sweat it! Making your woodworking projects shine starts with understanding the right tools. We’re going to break down the difference between a face mill and a fly cutter for wood in a way that makes sense. Get ready to confidently choose the best tool for your next job!

Face Mill vs Fly Cutter for Wood: An Essential Choice for Your Workshop

As makers, we’re always on the lookout for ways to improve our craft. Achieving a perfectly flat and smooth surface on your wooden projects is crucial, whether you’re building fine furniture, creating intricate carvings, or simply preparing stock for the next step. Two common tools you might encounter when tackling this kind of work on a milling machine or a specialized setup are the face mill and the fly cutter. They both aim to flatten surfaces, but they do it in distinctly different ways, and understanding these differences is key to making the right choice for your project and your workshop.

Choosing between a face mill and a fly cutter for wood isn’t just a matter of preference; it’s about selecting the tool that will give you the best results for the task at hand, safely and efficiently. These tools can seem intimidating, especially if you’re new to milling operations. But once we demystify them, you’ll see how they can become invaluable assets in your woodworking arsenal.

What Exactly is a Fly Cutter?

Imagine a single, very sharp blade mounted on an arm, spinning around a central point. That, in essence, is a fly cutter. Typically, it consists of a sturdy body, a mechanism to hold a single cutting tool (often a high-speed steel bit or a carbide insert), and an adjustable arm or cutter body that extends the cutting edge outwards. As the fly cutter spins in your milling machine’s spindle, this single cutting edge sweeps across the surface of the workpiece, shaving off material.

The magic of a fly cutter lies in its simplicity and precision for certain tasks. Because it uses just one cutting edge, it can achieve a very smooth finish, especially when used with a sharp, well-maintained cutter. This makes it excellent for surfacing projects where a mirror-like finish is desired. Think of it as a giant, precisely controlled chisel that moves in a perfect circle.

How a Fly Cutter Works on Wood

When you use a fly cutter on wood, the single sharp edge rotates. You typically set the cutter’s overhang so that its path overlaps slightly with the previous pass. This ensures that the entire surface is covered and smoothed. The depth of cut is usually kept shallow to maintain a good finish and to avoid overloading the cutter or the machine.

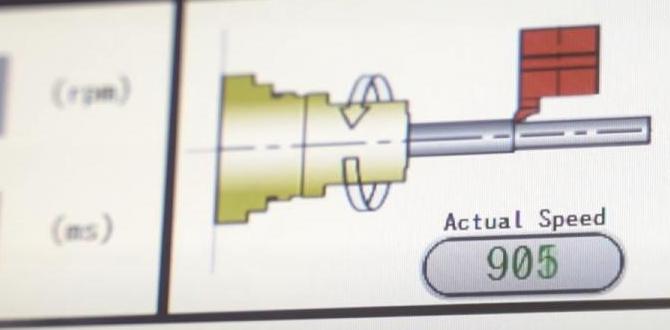

The rotation speed (spindle RPM) and the feed rate (how fast you move the workpiece or the spindle) are critical for achieving a good result. Too fast a feed rate or too deep a cut can lead to chipping, tear-out, or a rougher surface. With careful setup and operation, a fly cutter can leave a surface that is remarkably smooth, often requiring minimal or no further sanding.

Key Components of a Fly Cutter:

- Body/Holder: The main part that mounts into the milling machine spindle.

- Cutter Arm/Extension: Holds the cutting tool and allows for adjustments.

- Cutting Tool: Usually a single, sharp blade (e.g., HSS bit, carbide insert).

- Adjustment Mechanism: Allows precise positioning of the cutter edge.

What is a Face Mill?

Now, let’s talk about the face mill. If a fly cutter is like a single powerful hand tool, a face mill is more like a power tool with multiple cutting bits. A face mill is a type of milling cutter designed to machine flat surfaces. Instead of a single blade, it has a robust body that holds multiple cutting inserts or teeth around its periphery and often on its face. These inserts are typically made of carbide, which is much harder and more durable than high-speed steel, allowing for aggressive material removal.

Face mills come in various designs, but the most common type for general-purpose milling has inserts arranged around the edges and sometimes the top surface of the cutter head. As the face mill rotates, all these cutting edges engage the workpiece simultaneously, creating a wide cutting path. This multi-cutter approach is what gives face mills their power.

How a Face Mill Works on Wood

When a face mill is used to mill wood, it effectively takes many small bites at once. Each insert is responsible for removing a small amount of material, but because there are many of them working together, the overall rate of material removal can be very high. This makes face mills ideal for taking off significant amounts of material quickly, like flattening a very warped or oversized board.

The setup for a face mill requires careful consideration of the inserts. They need to be sharp, properly seated, and all at the correct height. If one insert is set higher than the others, it will take a deeper cut, potentially damaging the workpiece or the tool. The robust nature of face mills means they can handle deeper cuts and faster feed rates compared to fly cutters, making them efficient for roughing operations.

Key Components of a Face Mill:

- Body/Head: The main casting that holds the inserts and mounts to the spindle.

- Inserts: Replaceable cutting teeth, usually made of carbide.

- Insert Pockets: Precisely machined locations where the inserts are held.

- Clamping Mechanisms: Screws or wedges that secure the inserts.

Face Mill vs Fly Cutter for Wood: Comparing Key Differences

When you’re deciding which tool is right for your project, it’s helpful to see them side-by-side. They each have strengths and weaknesses that make them better suited for different jobs. Let’s break down the key differences:

| Feature | Face Mill | Fly Cutter |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Cutting Edges | Multiple (typically 4 to 20 or more) | Single |

| Material Removal Capacity | High – designed for aggressive stock removal. | Moderate – best for lighter cuts and finishing. |

| Surface Finish | Can be good, but often leaves tool marks requiring further sanding. Depends heavily on insert sharpness and number of flutes. | Can achieve an exceptionally smooth, almost polished finish with a sharp cutter. |

| Tooling Cost | Higher initial tool cost, but individual inserts are replaceable and can be cost-effective in the long run. | Lower initial tool cost, but the single cutter may need sharpening or replacement more frequently, depending on material. |

| Complexity of Setup | More complex. Inserts need proper seating, alignment, and clamping. Tool geometry is critical. | Simpler setup. Primarily involves positioning and securing the single cutter. |

| Rigidity & Stability | Very rigid and stable due to multiple cutting edges and robust design. | Can be less rigid, especially with longer extensions. |

| Speed (RPM & Feed) | Can often run at higher spindle speeds and feed rates due to multiple cutters sharing the load. | Typically run at lower RPMs to maintain control and finish. |

| Ideal Use Cases on Wood | Flattening very warped boards, roughing large surfaces, removing significant material quickly. | Finishing passes for smooth surfaces, surfacing to final dimensions, achieving a high-quality finish with minimal sanding. |

| Common Material | Carbide inserts are standard for durability. | Can use HSS bits or carbide inserts. |

When to Choose a Fly Cutter for Woodworking

A fly cutter is your go-to tool when the primary goal is surface finish and precision calibration. If you’ve got a relatively flat piece of wood but need to bring it to an exact thickness without roughing marks, a fly cutter is your best friend. It’s akin to using a precisely tuned planing blade on a large scale.

Here are scenarios where a fly cutter shines:

- Achieving a Fine Finish: When you want a surface so smooth that sanding is almost an afterthought, a sharp fly cutter excels. This is crucial for projects where the wood will be visible and touchable, like tabletops, cabinet faces, or decorative panels.

- Working with Softer Woods: Softer woods can be prone to tear-out with aggressive cutting. A fly cutter, with its single, clean shearing action, can often provide a much cleaner cut on these materials.

- Surfacing to Final Dimensions: If you need to bring a piece of wood down to a very specific thickness after it’s been dimensioned by a jointer or planer, a fly cutter offers the control.

- Lower Initial Investment: For hobbyists or those just starting with milling operations, a fly cutter can be a more affordable entry point compared to a substantial face mill.

- Simpler Tool Changes: Swapping out a single cutter bit on a fly cutter is generally quicker and easier than changing multiple inserts on a face mill.

Working with a fly cutter requires patience. You’ll likely be making multiple passes, each one removing just a tiny bit of material. This meticulous approach is what yields that superior finish. Always ensure your cutter is extremely sharp; a dull fly cutter will lead to burnishing rather than cutting, leaving a poor surface and increased strain on your machine.

When to Choose a Face Mill for Woodworking

A face mill enters the picture when you need to get the job done quickly and efficiently, especially when there’s a significant amount of material to remove. Think of it as the workhorse of surface machining. If you have a board that’s significantly warped, cupped, or oversized, a face mill is the tool that will tackle the bulk of the correction work.

Consider a face mill for these situations:

- Aggressive Material Removal: When you need to flatten a severely warped board or reduce the thickness of a piece significantly, the multiple cutting edges of a face mill are indispensable. They can remove material much faster than a fly cutter.

- Roughing Operations: For initial flattening and dimensioning of rough stock, a face mill is the ideal choice. It prepares the wood for subsequent finishing steps.

- Hardwood Machining: While it depends on the specific wood, tougher hardwoods can sometimes be better handled by the robust carbide inserts of a face mill, especially when removing more material.

- High-Volume Production: If you’re producing multiple identical parts or working in a production environment, the speed and efficiency of a face mill are invaluable.

- Durability and Longevity: Carbide inserts are incredibly hard and wear-resistant, meaning a face mill can often handle more machining hours before needing servicing compared to a simple fly cutter bit.

Using a face mill effectively on wood involves managing the cutting forces. You want to ensure your machine is rigid enough to handle the load. Proper insert selection and sharpness are still crucial, but the focus shifts slightly from achieving a perfect finish on the first pass to efficiently bringing the part close to its final dimensions. You can explore resources from organizations like the Woodworking Network or consult manufacturers’ guides for specific recommendations on feeds and speeds for different wood types and cutters.

Setting Up and Using Your Chosen Tool Safely

No matter which tool you choose, safety and proper setup are paramount. Mishandling these tools can damage your workpiece, your machine, or even cause injury.

Fly Cutter Setup and Operation Tips:

- Mounting: Ensure the fly cutter body is securely mounted in your milling machine’s spindle.

- Cutter Adjustment: Adjust the cutter bit position so that the cutting edge is perfectly centered and extends just beyond the body. Ensure it’s set to take a light cut.

- Workpiece Clamping: Securely clamp your wood workpiece to the milling machine table. Overhanging pieces are a major hazard.

- Depth of Cut: Start with a very shallow depth of cut, perhaps just a few thousandths of an inch for wood.

- Feed Rate: Use a moderate feed rate. Too fast can cause tear-out; too slow can burn the wood.

- Pass Overlap: Ensure each pass slightly overlaps the previous one.

- Spindle Speed: For wood, typically lower RPMs (e.g., 500-1500 RPM) are recommended to avoid burning and ensure a clean cut.

Face Mill Setup and Operation Tips:

- Mounting: Mount the face mill securely in the spindle.

- Insert Inspection: Check that all inserts are sharp, undamaged, and properly seated in their pockets. Ensure they are all at the same height. This is critical! One misaligned insert can ruin the cut.

- Workpiece Clamping: Rigorously clamp the workpiece. Face mills exert significant forces.

- Depth of Cut: Determine the appropriate depth of cut based on the wood type, the number of inserts, and your machine’s rigidity. For initial passes on warped lumber, you might start with 1/8″ to 1/4″ or more, depending on the material and machine capacity.

- Feed Rate: Use a feed rate that allows each insert to take a manageable chip.

- Spindle Speed: Consult charts or your machine’s capabilities. Higher RPMs can be used with efficient chip evacuation.

- Chip Evacuation: Ensure your machine has good dust collection or chip removal to prevent chips from being recut.

“Safety in woodworking, as in metalworking, comes from knowledge and practice,” notes the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) regarding woodworking safety. Always wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE), including safety glasses or a face shield, hearing protection, and dust masks. Never wear loose clothing or jewelry that could get caught in moving parts.

Maintenance and Care for Your Milling Tools

Even the best tools need care to perform at their peak. Both face mills and fly cutters require specific maintenance:

Fly Cutter Maintenance:

- Sharpening: The single cutter bit is the heart of the fly cutter. It needs to be kept extremely sharp. Depending on the material and how often you use it, you may need to grind or hone the bit regularly. For carbide inserts, follow the manufacturer’s recommendations for honing.

- Cleaning: After each use, clean the tool body and the cutter holder to remove any wood dust, resin, or debris.

- Storage: Store the fly cutter in a protective case or holder to prevent damage to the cutter and the tool itself.

Face Mill Maintenance:

- Insert Inspection: Before and after each use, inspect the inserts. Look for chipping, dullness, or signs of wear.

- Insert Replacement: When an insert becomes dull or damaged, replace it. Make sure the new insert is correctly seated and clamped. Sometimes, if one insert is chipped, you might need to replace all of them to maintain balance and consistent cutting.

- Cleaning: Clean the face mill body, especially the insert pockets, to ensure proper seating of new inserts. Resin buildup can be cleaned with appropriate solvents.

- Storage: Store face mills carefully to protect the carbide inserts from accidental damage.

Proper maintenance not only ensures that your tools perform well but also significantly extends their lifespan and reduces the risk of accidents caused by tool failure. Remember, sharp tools are safer tools because they require less force to cut.

The Verdict: Which Tool is Right for You?

So, after weighing the pros and cons, which tool should you choose for your woodworking projects? The answer, as is often the case in the workshop, depends on your specific needs and the task at hand.

- For the Hobbyist Seeking a Superior Finish: If your primary goal is to achieve glass-smooth surfaces on fine furniture or decorative pieces, and you don’t mind taking extra, careful passes, the fly cutter is likely the better choice. Its simplicity and ability to produce a highly refined surface make it ideal for finishing work.

- For the Maker Needing to Remove Significant Material: If you frequently work with rough lumber that needs substantial flattening or dimensioning