Wood lathe workholding techniques unlock precise turning by securely gripping your workpiece. Mastering common methods like chucks, faceplates, and between-centers ensures stability, safety, and beautiful results for all your projects.

Getting your wood securely held on the lathe, known as workholding, is one of the most fundamental skills for any woodturner. When your wood isn’t held firmly, it can vibrate, tear, or even fly off the lathe – and that’s dangerous for you and your project. It’s a common stumbling block for beginners, leading to frustration and imperfect results. But don’t worry! With the right techniques and a bit of practice, achieving a solid grip is straightforward. This guide will walk you through the essential wood lathe workholding methods, helping you turn with confidence and create stunning pieces.

Wood Lathe Workholding: The Foundation of Great Turning

Workholding on a wood lathe is all about securely attaching your workpiece (the wood you’re turning) to the lathe’s headstock, which provides the rotational power. The method you choose depends on the shape and size of your wood, the type of project you’re making, and the tools you have available. A well-held piece is crucial for safety, allowing you to remove material efficiently and accurately. Without it, you risk damaging your wood, your tools, and yourself.

Think of it like this: if you were trying to carve a statue, you wouldn’t want the stone wobbling around, would you? The same applies to woodturning. Secure workholding allows for clean cuts, sharp details, and the peace of mind that comes with knowing your project is stable.

We’ll explore the most common and effective workholding techniques. Mastering these will open up a world of possibilities for your turning projects, from delicate bowls to sturdy table legs and everything in between.

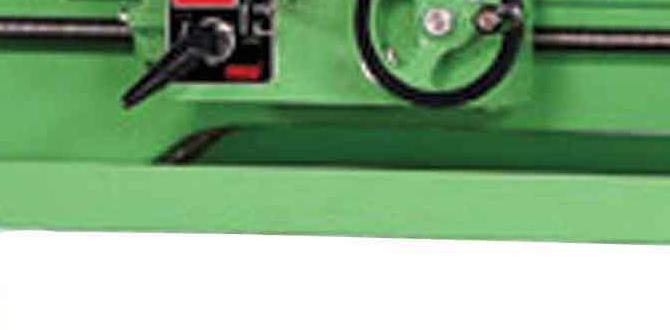

Understanding Your Wood Lathe’s Drive System

Before diving into specific workholding methods, it’s helpful to understand the basic components of your lathe that are involved:

- Headstock: This is the part of the lathe that houses the motor and spindle. It provides the rotational power to your workpiece.

- Tailstock: The tailstock moves along the bed of the lathe and is used to support longer workpieces or to hold tools like drill bits for boring.

- Spindle Threads: Most lathe headstocks have threaded spindles where workholding devices like chucks and faceplates are attached. These threads are typically standardized (e.g., 1″ x 8 TPI is common in North America), but it’s essential to check your lathe’s specific threading.

- Centers: These are pointed or cup-shaped accessories that fit into the headstock and tailstock to grip the wood.

Knowing these parts will make understanding the workholding techniques much easier. Let’s get to the good stuff – how to actually hold that wood!

Essential Wood Lathe Workholding Techniques

There are several ways to hold wood on the lathe, each with its own strengths and applications. We’ll cover the most important ones for beginners.

1. Between-Centers Turning

This is perhaps the simplest and most fundamental workholding method. It’s perfect for squaring up and shaping cylindrical stock before using other methods or for making projects like spindles and table legs.

How it Works:

A drive center is fitted into the headstock spindle, and a live center (which revolves with the workpiece) is fitted into the tailstock. The wood is then held firmly between these two points. The drive center has teeth that bite into the wood to transfer rotational power, while the live center supports the other end.

Tools Needed:

- Headstock Drive Center: Usually a spur drive or pin locator style.

- Tailstock Live Center: A conical, pointed center that allows the wood to spin freely.

- Tailstock: Positioned and locked correctly.

- Wood Screw (optional for some setups): To aid in securing the wood to the drive.

Steps for Between-Centers Turning:

- Prepare Your Stock: Cut your wood to a length slightly longer than the desired final piece. Ensure the ends are relatively flat.

- Install the Drive Center: Screw the drive center firmly into the headstock spindle.

- Position the Tailstock: Align the tailstock with the headstock and extend the quill so the live center can engage the end of your workpiece.

- Mark the Center: Find the exact center of both ends of your wood. This is crucial for a balanced and stable turning experience. You can use a compass or a center finder.

- Position the Wood: Place the wood between the headstock and tailstock, aligning the marked centers.

- Engage the Live Center: Advance the tailstock quill to press the live center firmly into the end of the wood. You want a good bite but not so much pressure that you’re stressing the wood. A general rule is to have about 1/8th to 1/4th inch of the live center shank engaged.

- Lock the Tailstock: Securely lock the tailstock in place.

- Disengage Belt: Always ensure the lathe belt is disengaged before turning on the motor.

- Initial Slow Spin: Turn the headstock by hand to ensure the wood clears everything and doesn’t wobble excessively.

- Turn On Lathe: Start the lathe at a very slow speed (e.g., 500-600 RPM for most medium-sized pieces).

- Gradually Increase Speed: As you turn, you can gradually increase the speed, listening for any unusual noises or vibrations. If you hear or feel anything, stop immediately and check your setup.

Pros:

- Simple and inexpensive.

- Ideal for initial squaring and shaping of blanks.

- Works well for long, slender pieces like spindles.

- Minimal risk of the workpiece flying off if properly set up.

Cons:

- Difficult to turn the entire surface of a large or asymmetrical blank (like a bowl blank) without creating a significant “throw weight” or imbalance.

- Requires careful centering of the wood.

- Leaves a pointed indentation at each end that needs to be dealt with later.

2. Faceplate Turning

Faceplates are simple, sturdy discs that screw onto the lathe spindle and provide a mounting surface to attach larger or irregularly shaped pieces, especially for bowl turning. They are excellent for turning the outside of bowls or for creating items mounted off-center.

How it Works:

A faceplate has a threaded hub that screws onto the lathe’s headstock spindle. The plate itself has bolt holes and sometimes slots around its circumference. Your workpiece is then attached to the faceplate using screws, bolts, or a combination of both.

Tools Needed:

- Faceplate: Ensure the thread matches your lathe spindle.

- Wood Screws: Use screws long enough to get a good grip in your workpiece, but not so long they go all the way through.

- Drill and Drill Bits: For pre-drilling screw holes.

- Wrench or Chuck Key: For tightening the faceplate onto the spindle.

- Center Finder (optional): To help align your workpiece.

Steps for Faceplate Turning (Bowl Blank Example):

- Prepare Your Blank: Cut your wood into a rough disc or shape. For bowl turning, rough out a circular shape that is slightly larger than your intended final bowl.

- Mark Mounting Points: Find the center of your blank. Mark points where you will attach the faceplate. For a round bowl blank, this will be the geometric center.

- Attach Faceplate to Lathe: Screw the faceplate onto the lathe’s headstock spindle. Tighten it securely.

- Position Blank on Faceplate: Align the center of your blank with the center of the faceplate.

- Mark Screw Holes: With the blank held in place (you might need a helper or clamps initially), mark the positions of the faceplate’s screw holes onto the blank.

- Pre-drill Screw Holes: Remove the blank from the faceplate. Drill pilot holes at the marked locations. The depth of these holes should be less than the length of your screws.

- Attach Blank to Faceplate: Place the blank back onto the faceplate, aligning the pilot holes. Drive screws through the faceplate holes into the blank. Ensure they are snug but avoid overtightening, which can split the wood. For structural integrity, some turners use a few bolts with large washers that go through the faceplate, the wood, and into the threaded rod that screws into the faceplate’s center for bowl turning.

- Secure the Lathe: Ensure the tailstock is out of the way or removed if it obstructs turning.

- Check Clearance and Balance: Turn the assembly by hand slowly to ensure nothing is caught and to feel for gross imbalances. If turning a very irregular blank, start at very low speeds.

- Turn on Lathe: Start at a low speed and gradually increase as you gain confidence and as the blank becomes more balanced through turning.

Pros:

- Excellent for bowl blanks and larger pieces.

- Provides a very secure and rigid mounting.

- Allows for off-center turning (eccentric turning) by shifting the blank’s mounting points.

- Screws tend to be cheaper than chuck jaws.

Cons:

- Requires drilling into your workpiece, leaving screw holes that need to be filled or accounted for.

- Can be difficult to find the exact center, especially on irregular pieces.

- Risk of “throw” (unbalanced rotation) if the blank is significantly asymmetrical and turned at high speeds.

- Faceplates can be heavy and require strong spindle threads.

For more detailed advice on securely mounting bowl blanks, resources like the American Association of Woodturners (AAW) offer valuable insights into safe practices. You can find more information on their website, aaw.org.

3. Chucks

Lathe chucks are arguably the most versatile and widely used workholding devices for woodturners. They come with jaws that can be opened or closed around a workpiece, offering a wide range of gripping possibilities.

Types of Chucks:

Wood lathe chucks are typically scroll chucks, meaning they have a scroll gear mechanism that ensures all jaws move in unison and at the same rate. They come with different sets of jaws designed for various types of gripping.

Common Jaw Types and Their Uses:

| Jaw Type | Grip Type | Typical Use | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Jaws (e.g., CS, SC, SP8) | External grip (wrap around), Internal grip (expand into a hole) | Rough turning bowls, spindles, tenons, jam chucks, tenon grips | Versatile, widely applicable for basic turning | Can crush soft wood if overtightened; requires tenons or holes |

| Dovetail Jaws | External grip (specifically for the dovetail shape of chuck adapters), Internal expansion (into corresponding dovetail recesses) | Holding bowls securely after they’ve been reversed from the faceplate, gripping tenons with a dovetail profile | Excellent grip on specific shapes, very secure for reversed bowls | Less versatile for general purposes; requires specific workpiece preparation |

| Cole Jaws | External grip (flat surface), Internal grip (suction/friction, often with a rubber ring) | Holding dry, flat-faced workpieces (e.g., lids, platters), gripping irregular shapes | Good for delicate or dry wood, can hold without damaging surfaces | Can be tricky to get a perfect seal for suction; not ideal for green wood or heavy cuts |

| Pin Jaws / Micro Jaws | Internal expansion (small holes), External grip (very small workpieces) | Small delicate items, finials, miniature work, tiny tenons | Ideal for small, precise work | Limited capacity, can’t handle large or heavy pieces |

| Jaws for Special Purposes | Various (e.g., vacuum chuck adapters, large external grips) | Specific tasks like vacuum chucking or gripping very large bowls | Specialized grip for unique needs | Often expensive, not for general use |

Steps for Using a Chuck:

- Mount the Chuck: Ensure the chuck’s spindle thread matches your lathe. Screw it onto the headstock spindle and tighten securely.

- Select Appropriate Jaws: Choose the jaw set best suited for your workpiece and planned operation (e.g., standard jaws for gripping a tenon).

- Prepare the Workpiece: This usually involves creating a “tenon” (a cylindrical projection) on your workpiece to be gripped internally by the chuck jaws, or a recess to be gripped externally. Alternatively, you might be gripping the outside of a rim or lid. For bowl blanks, you’ll often create a mortise (an internal recess) to grip.

- Mount the Workpiece: With the lathe OFF, open the chuck jaws using the chuck key until they are wide enough to accept your tenon or recess. Insert the tenon or workpiece into the chuck.

- Grip the Workpiece: Tighten the chuck jaws using the chuck key. As you tighten, the jaws will move inwards, gripping the tenon or workpiece. Tighten firmly but be mindful of the wood’s strength to avoid crushing it.

- Test Grip: Turn the lathe assembly by hand to ensure the workpiece is secure and clears all parts of the lathe.

- Start Lathe at Low Speed: Engage the belt, and start the lathe at a very low RPM. Listen for any unusual sounds or vibrations.

- Gradually Increase Speed: As you confirm stability, you can slowly increase the speed.

A well-chosen chuck and jaw set can handle a vast majority of woodturning tasks. For beginners, a standard set of jaws is an excellent starting point. Reputable manufacturers like Vicmarc, Oneway, and Nova offer quality chucks.

4. Jam Chucks

A jam chuck is a custom-made, often sacrificial, form that is mounted on the lathe and grips the workpiece by friction or by wedging action. They are incredibly useful for holding pieces that can’t be easily gripped by standard chuck jaws or for reversing a bowl to turn the base.

How it Works:

You create a jam chuck from a piece of scrap wood. This chuck is mounted to the lathe, often on a faceplate or a simple screw chuck. Then, your workpiece is pressed into or around the jam chuck. For reversing bowls, you drill a hole in the faceplate-mounted bowl, and the jam chuck is turned to fit snugly into that hole. Friction and a snug fit hold the bowl.

Tools Needed:

- Scrap wood for the jam chuck

- Chuck or Faceplate

- Lathe tools for shaping the jam chuck

- Wood screws (optional, for securing the jam chuck)

- Sandpaper

Steps for Creating and Using a Jam Chuck (for Reversing Bowls):

- Turn the Outside of Your Bowl: First, mount your bowl blank on a chuck or faceplate and turn the outside to its final shape. While it’s mounted, create a tenon or a recess on the rim that matches the size of your intended jam chuck.

- Create the Jam Chuck: Mount a solid block of scrap wood onto the lathe spindle (using a faceplate or screw chuck). Shape this block so it has a recess that will perfectly cradle the tenon you created on your bowl. You want a very snug fit – a friction fit. As you turn the jam chuck, you’re creating a custom-shaped “holder” for your bowl.

- Test the Fit: Remove the jam chuck from the lathe and test fit it against the tenon on your dried bowl. Remove material incrementally if needed until it’s snug.

- Mount the Jam Chuck: Re-mount the jam chuck securely onto the lathe spindle.

- Mount the Bowl: With the lathe OFF, carefully press the bowl’s tenon into the recess of the jam chuck. You want it to be tight enough to hold without needing screws, relying on friction and the snug fit. For extra security, some turners will drive a couple of small screws through the jam chuck into the rim of the bowl, but these should be countersunk and ideally placed where they will be removed during shaping.

- Turn the Inside: With the bowl now securely held by the jam chuck, you can turn the inside and rim to its final shape, remove the tenon, and refine the base.

- Final Sanding and Finishing: Once